The Eleven Homes I've Had in Tokyo

An account of every place I've lived in Tokyo and why I moved in -- then out.

Last month I packed everything in my studio apartment into discarded watermelon boxes and moved it all 8km south in a rental van. I had done much harder moves in the past but I had also set aside time dedicated to those moves. This time, I couldn’t. Somehow both of my jobs synched up to be the busiest they would probably be all year and my move-out date landed gracelessly right in the middle of it. Somewhere in the vicious cycle of midnight writing deadlines and 8am shoots, I grasped for the time and energy to pack, turn off utilities, go to the city office, etc.

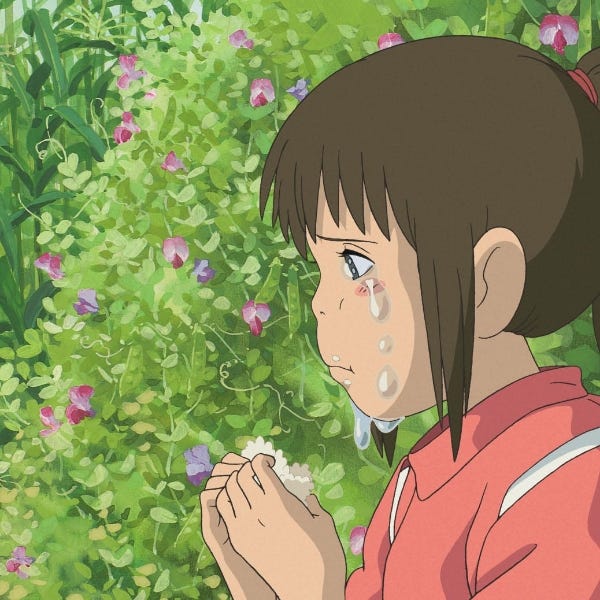

The soul sapping sleep deprivation mixed poorly with the forlorn feeling I get sitting alone in a sea of indifferent objects. I cried seven times in one move day, which must be a personal record because I only cried once during a far more harrowing international move. Pretty much anything would set me off but nothing made me bawl as hard as biting into an egg sandwich. I truly felt like the most pathetic person alive. I also felt like I was cosplaying the scene in Spirited Away where Chihiro eats a rice and ball starts sobbing. This comparison made me cry-laugh so I took a selfie. Chihiro below for comparison.

Just like Chihiro, I can also get on with it after a cathartic cry. I packed everything up but of course, that’s only half the battle of moving.

I remember the first car I ever drove in Tokyo was a gigantic moving van. This was for my seventh move. I ignored the GPS’s warning to watch out when turning into a very narrow street and ended up hitting a wall.

The only thing I hate more than driving large vehicles is moving large pieces of furniture. The thought of losing a toe terrifies me. Luckily, my boyfriend came on move day and swiftly took over the operation. He isn’t phased by driving a van in residential Tokyo. He is also, god bless, not afraid to lug a washing machine down four flights of stairs by himself. I was grateful to him. Half a day later, I was all moved into my new space and collapsed on the couch for the evening.

However, at some point I realized that I had made a very stupid error by not hiring a moving company. Why didn’t I think of that? I forget that I am an adult now who can hire people to do things I am very bad at instead of making myself miserable trying and doing a bad job (which reminds me, I really need an accountant and website designer). I made up my mind to hire professionals next time I move…….which will be in December of this year, five months from now.

Which is insane, I know.

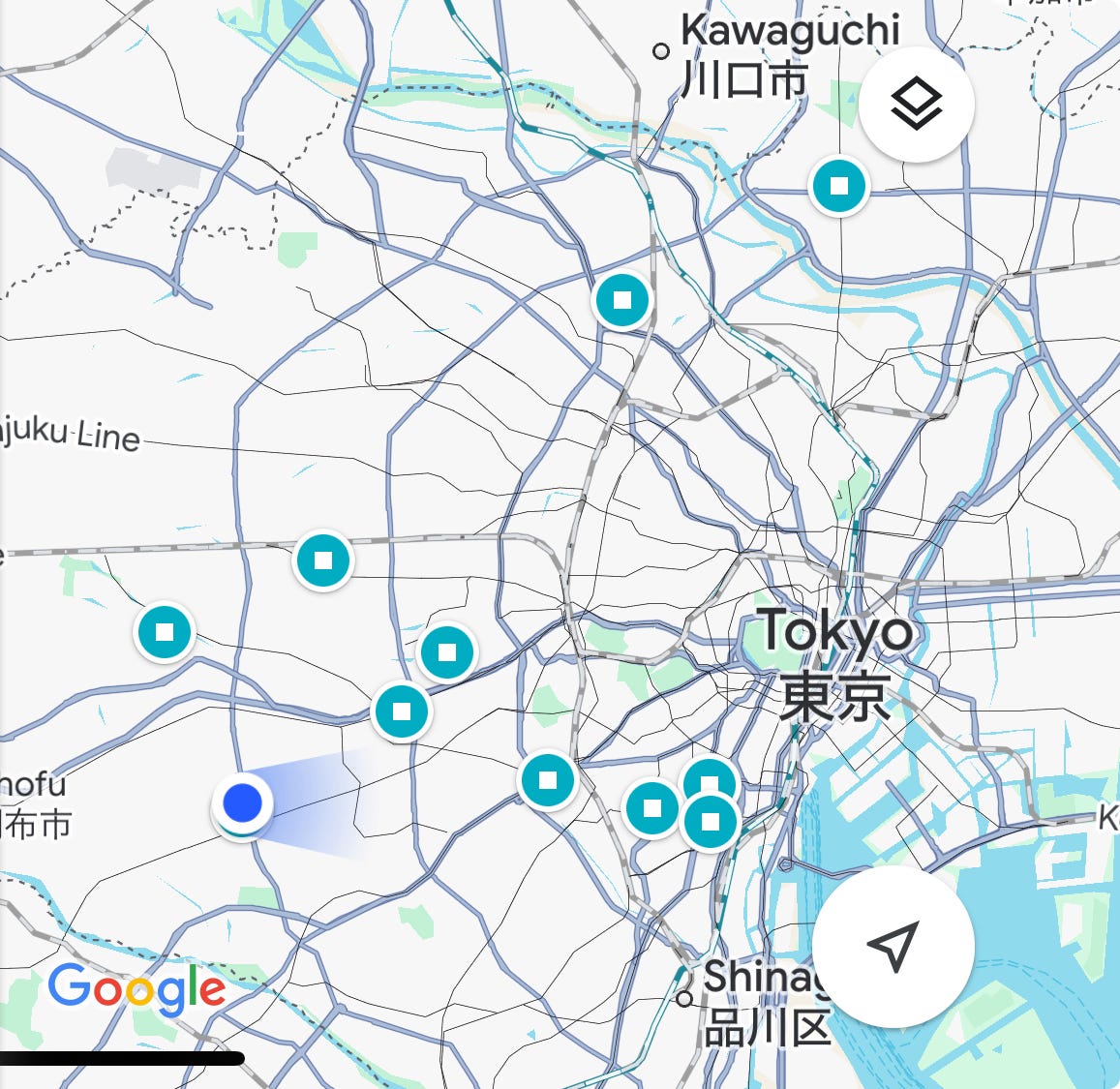

Here’s what is more insane. I counted how many homes I’ve had in Tokyo, and I was shocked when I ran out of fingers — I have moved a total of eleven times. By the end of the year, it will be twelve.

I’ve lived in Tokyo for about eight years now, so on average, I move at a rate of 1.5 times a year. When I tell people this, they think I am out of my mind and I have to agree. They assume it is because I love moving or get bored of living in one place too long. I do get restless easily but that is never the reason why I move. It’s not worth moving just because I feel like it. Moving is hellish and the upfront costs of moving in Japan are expensive. The realtor fee, key money, deposit and reikin or “thank you money” will set you back at a minimum of 300,000 yen.

This is a complete sidebar but I just thought of the origins of “thank you money”. Back then children almost always lived with their families until they got married, whether you were male or female. This is still pretty common today. But at the turn of the 20th century unmarried adults started going to the city to study or work and had to live away from home. Parents often sent their children to live in homes that had a landlord who also doubled as a surrogate parent, called an ooyasan. These kindly landlords looked over the young adults; they made sure they were adjusting to city life and not getting into trouble. The presence of an ooyasan was incredibly reassuring to the real parents, so to show their gratitude, they would pay the ooyasan “thank you money” for taking care of their kid. Nowadays it’s rare to even know the name of your landlord, let alone have them check in to make sure you’re getting enough to eat. The practice of paying reikin is completely detached from its original sentiment but most places still require you to pay reikin anyway…although I doubt anyone pays it with even a grain of gratitude. I definitely don’t and think it’s a greedy practice that needs to be abolished.

Okay, back to why I’ve had to pay reikin more times than anyone I know (although I certainly did not pay it every time).

Honestly, I had a hard time finding a nice neat pattern to rationalize all the moves. I decided to do some investigating — I took out old pictures, skimmed my journals, and reflected on the past to piece together not just a story of my many apartments, but the story of my life in Tokyo — the circumstances and desires and luck (good and bad) that rose and fell with each move.

I hopscotched apartments because of everything from an eccentric older couple, a Michelin chef, an almost-kidnapping, a modeling gig, a true crime podcast, and occasionally, love.

*Names have been changed to protect the identity of the people involved.

Itabashi Dorm - 2013

I moved into an all-girls dorm when I first arrived in Tokyo for university at 18. Or rather, I went to university so I could be in Tokyo. So you can imagine my agitation when I found out curfew was at 10pm and all vices such as drinking, smoking and boys were strictly prohibited. Instead of rushing home for curfew I frequently bar hopped until first train, maybe slept a couple hours in a manga cafe, and then went home to freshen up before my morning class.

I was probably not very beloved among staff. I always came back after first train reeking of poor choices. One time my friend and I set off the emergency alarm at 3am on a Wednesday, waking up seven floors of bewildered college girls and staff. I also came to the front desk once with my finger in a sock dripping with blood after I cut off the tip of my finger — I calmly asked for a band-aid.

Despite there being a clash in lifestyle between me (thrived on chaos) and the dorm (concerned with safety and order), there were things I really liked — the piano room where I could practice, a cafeteria with inexpensive and delicious foods, and other girls I could socialize with. After one semester, I was given the option to extend my residence but I said no way. I found two other like-minded girls who were also sick of the dorm, and over shisha we decided to move into a new place together.

Adachi House - 2013

Everyone told us not to move to Adachi. They insisted it was the ghetto of Tokyo, the most dangerous place in the city. We laughed at them. Laura, who was ex-navy, was unfazed..she had just been at war, after all. And Jenna had lived in enough places in the US to know what a true ghetto was. I was from rural Vermont so knew nothing about dangerous neighborhoods, but also distrusted the Japanese meter for what was dangerous or not — I thought everyone was being dramatic.

So without any hesitation the three of us moved to a dingy neighborhood in Adachi-ku. The house was surrounded on all sides by other houses and got very little natural light. It was far from the station and also a long commute to school. But it was large and only 30,000 yen a person (roughly $300 a month) which was honestly the maximum price for rent that I could afford. We found a used kotatsu which was the only piece of furniture in the living room/ kitchen. Laura and I were so broke we ate nabe or stir fried garlic tops most nights, but somehow always had a budget for a handle of whiskey and strong zeros.

I was going to school, interning at the Japan Times, and working part-time as a waitress. I was always home late but I loved coming home — Jenna would be sitting in the kitchen with her Amy Winehouse eyeliner watching MMA fights and Laura would come stumbling home from Nichome with some racey stories from the gay district. We would often go to the local wine bar run by a retired salary man. He traveled the world collecting wines and served them for cheap to the down to earth locals and fed us free garlic bread.

Jenna and Laura were the perfect roommates but the location was wearing us all down — the remoteness, the dinginess, the strange encounters we would have with locals. There was one particularly distressing man who had a penchant for chasing Jenna down the street on his bicycle with a basket full of rotting cabbage. You could smell him coming before you saw him which was your cue to start running.

The cabbage man was mostly harmless but I soon found out people were wary of Adachi. One day, on my walk back from last train, I came across a large van parked in front of the elementary school. A man wearing a black button up with poorly dyed, orange hair got out of the passenger’s side. He averted his gaze from mine and shifted back and forth on the balls of his feet. “Do you know where the elementary school is?” he asked me, which is a strange thing to ask someone at 1am, especially when the elementary school is clearly in view. I picked up my pace and then heard three doors bolt open behind me as more poorly dyed heads appeared in the dark street. I sprinted, yelling “LAURAAA!” as I turned sharply into the mercifully close cul-de-sac where our house was. No one was there when I got home. I bolted the door and called the police. They searched for the van but didn’t find one.

A week later, I was at my friend’s house in Saitama and had basically forgotten about the incident. He casually asked if I’d seen that Adachi had been in the news lately; there had been cases of people being kidnapped into human trafficking. I felt frost bite into my stomach and I told him what happened. It was the same as the news: the van, the young delinquents, the ambush. “Maybe it’s time for you to move,” he said. Within a month, Jenna, Laura and I were out of Adachi and gone our separate ways.

Luxury Azabujuban Apartment/ Office - 2014

For unrelated reasons, Jenna left Japan and Laura moved in with another friend who had an open room. I do not remember what conversation lead to my next move, exactly, but an elderly couple I was friendly with since high school proposed a living situation to me — for not very much money, I could live in their apartment turned office in Azabujuban. All I had to do was a couple hours of free office work a day. Again, I was too poor to afford a real move on such short notice and this sounded like a good deal until I could save up for a more private living accommodation. It’s also worth nothing that Azabujuban is notorious for being the most expensive neighborhood to live in in all of Japan. Not only would I get to live in Azabu-Juban, I would also be living in wan apartment you could get to using the elevator from the station. For a short amount of time, why not?

I am very grateful to the couple for trusting a teenager to inhabit their space, but living in an office was as difficult as you might imagine — I had to eliminate any signs of life before their employees came in at 9am and also be showered, dressed and ready to work. The couple were kind but highly conservative and quick to criticize the way I dressed and nosy about my whereabouts. During this time, I began working at an Italian restaurant downstairs run by a Michelin starred chef. I also began teaching him English five days a week over coffee at 8am. I mentioned to the chef that I was getting exhausted living at the office and was looking for a place to live in a less expensive neighborhood. The next day, he showed up with a page printed from a realtor of a studio apartment in the area — very small but also very cheap. And most importantly, all my own. “Please keep working for me,” he said. My internship, college and job(s) were all within 15 minutes of the apartment. I agreed on the spot.

Closet in Minami-Azabu - 2015

I quit college and starting working full time to afford more college in the US, but that’s another story. I was barely home and worked three jobs to save up money — I continued teaching English, I wrote for Spotify and I worked five days a week at a night club. My apartment had room for a bed and a mini fridge filled with beer and Pocari sweat. I didn’t have enough space to cook and ate at the falafel stand on the first floor of the apartment building almost every day. I worked and on the weekend I went out. I was barely ever home.

I lived there for eight months and then left for the states, ending my first two and a half year stint in Tokyo. I honestly didn’t think I would ever come back.

Hiroo Hotel - 2016

One year later, I wasn’t exactly back but I was in Tokyo for the summer. A person I fell in love with a week before I left Japan was now my boyfriend, against all odd and circumstances. We’ll call him Oliver. I needed to make more money (the ongoing struggle of putting yourself through college) and Oliver had work opportunities in Tokyo — so we found ourselves living in a hotel that his modeling agency provided, sharing the smoking space with minor celebrities and a big shot musician from the 90s. It was full of other male models from his agency as well — I felt like a dwarf living amongst these tall, angular Tolkein-esque elves. I was neither famous nor runway material but the other inhabitants and staff welcomed me none-the-less.

Perhaps this place, only home for three months, doesn’t count as much as the others, but I remember it vividly. Thanks to Oliver it was the first Tokyo neighborhood I really fell in love with. While I rarely frequent the same place twice, Oliver wanted to go to the same cafe for a late breakfast everyday and have the exact same thing — a cappuccino, an English breakfast and a rolled cigarette. His enthusiasm for the cafe never wavered and neither did the warm welcome from the staff. Much to his delight, they drew a new picture on his cappuccino every day. We often got little dessert for free. They loved him, and by extension, were nice to me. I also started getting personalized cappuccino art which was enough to convince me, someone who feels queasy at the mere thought of routine, to go every day. Hiroo was the first place I ever became a regular. In three short months, I discovered an entirely different way of belonging in a neighborhood. I loved the turtles in the park, the camera shop where we dropped off film, the yakitori spot we’d go to after a late night out. When we left, the staff at the cafe cried, Oliver cried, and I cried into my goodbye cappuccino because I never wanted to leave. I also had a feeling that even if I did come back, it would never be the same.

Start of Freelance Life in Daitabashi - 2019

Fast forward two years, four moves in Vermont and two major breakups later — I am merely passing through Tokyo on my way to South East Asia. I have some locations in Vietnam and Thailand lined up to live at while I teach yoga. But first, I decide to stay the winter in Hakone for a couple months to regroup and work at an onsen. The job is regimented and gives me a lot of time to reflect, just like I wanted. I wake up at 7am, work until noon, write and occasionally publish poetry then hang out with guests and coworkers the rest of the day.

Once spring comes, my old roommate Laura’s friend, a film director, invites me to stay with her in Tokyo until my flight — under one condition — I star in a promotion video she is shooting. I am not very confident about it since I don’t have any experience being shot in video. I have minimal modeling experience. She promises to help me. I do my first shoot and when you watch the video, you can tell the size of the cinematic Alexa camera is freaking me out. I look how I felt: stiff, uncomfortable, unsure why I was there and not someone who was actually a model. Even so, after the first shoot people start asking me if I’m interested in other modeling jobs. As always, I am broke so I take them. In one day, I make more than I usually make in half a month, maybe even a whole month. I think to myself that it would be good to do a job or two before I head to Vietnam — I could always use the money. But then the film director — we’ll call her Aurora — says, I have extra space and I could use a roommate, stay however long you’d like. And just like that, I became what I still am now: A freelancer.

I adored Aurora. She woke me up every morning at 9am by putting the The Dark Side of The Moon record by Pink Floyd on the record player. She made me coffee not knowing I didn’t drink coffee, but I drank it anyways and I still drink coffee every morning to this day. She also made me her signature breakfast dish — sunny side up with fried natto on rice. I still eat that at least a couple times a week. She taught me how to make an invoice, how to negotiate my day rate, what it takes to make a movie. I have never been a TV watcher but we watched TV every night and she was so passionate about it I grew to love TV.

Sometimes I’m a bit sad that our roommate situation crumbled like it did, but gratefulness eclipses any other feeling. For some reason Aurora saw something in me and took me in and taught me the ropes of the freelance industry. She lit a tiny fire inside me and sent me down my path like a lantern down a river.

Sasazuka During Covid - 2020

For some reason I find myself struggling to know what to say about my two years in Sasazuka. I moved in the week before covid hit the world. During this exact same week, Peter, who I was casually seeing, got deported from Japan. We decided he’d stay with me until his deportation day at the end of the month. But here’s the thing —because of covid, there were no more planes going to his home country. He ended up staying with me for eight months. Our relationship existed in the liminal space that was covid and his unknown deportation date. It was….bizarre.

But I think about the possibility of being quarantined alone the whole time and I’m not sure I would have liked that. I have lived with others since I was fourteen and I like having company. I am a social creature who, despite having very solitary tendencies, gets lonely easily. And Peter was a good house mate. He was clean, he cooked, he was always starting new art projects. He had a side gig doing back up vocals for karaoke machines so we’d often practice singing. This was actually a big step for me because I have always been shy about singing and he helped me learn to enjoy it.

One day, Peter surprised me with a bird from our friend’s animal sanctuary. Her name is Kyoko. I’m not exactly the ideal pet owner (as you can tell from this article) but I took her in anyways because I was quarantined and had a lot of time to rehabilitate her. I grew up with birds so I’m good with them. She went from being a biter who rarely left her cage to being….angry in a much more cuddly, social way. Kyoko is a lemon sized balled of petulance but I love her. She’s still with me.

Despite covid, I was lucky enough to get freelance work to pay rent. At some point Jake Adelstein found a poem I published while I was living in Hakone and hired me to edit his books. I also had a lot of free time which I dedicated to covid hobbies like color grading on DaVinci, making Indian curry from scratch, and playing my first ever video game, Zero Dawn Horizon (I was obsessed and didn’t leave the living room for a week. I barely ate. I have not played a video game since for fear of becoming an addict).

And what’s more, the Sasazuka apartment was my favorite Tokyo apartment yet; it was concrete with three floors connected by a spiral stair case. The first floor had a beautiful bathtub I could fill by pressing a button in the kitchen on the third floor. The second floor was basically a closet. And the third floor was the kitchen, bedroom and living room.

Peter eventually got deported for real and I lived alone after that. A year passed, covid was still at large, and I was getting restless. I felt ready to move out of Tokyo again and wanted to go back to grad school…this time to study psychology and psychedelics. I tearfully gave my bird to my best friend and neighbor, May. I did the hellish international move which was filmed by an YouTuber and got 500k views on Russian YouTube, of all places. I was able to move feeling at peace with myself and full of optimism for the future.

This is the one time I actually did move out for no reason other than, it was time to go.

Shibuya Apartment with Sweets Love Hotel View - 2022

I was only in the states for a week, still jet-lagged when Jake, who I had been editing for here and there, messaged me on Facebook with a job proposal — come back to Tokyo to work on a true crime podcast about missing people in Japan. The pay was decent, I loved cultural phenomenons and I had a background in journalism. It was a dream job. I bought a flight back to Tokyo right away.

Thinking I was just going to live in Japan for eight months until the podcast was over, I moved into a monthly, fully furnished apartment in Shibuya. The last thing I saw before I went to sleep at night was the glowing ice cream cone atop the Sweets love hotel.

I wasn’t the only one to move to Tokyo this time. Back in the US, my sister Amy had just graduated from university and was working at a coffee shop. She crashed her car and was living with our parents and was feeling a little hopeless about the future. I told her she should come stay with me in Tokyo for a little while — you don’t need a car, we have universal health care and you can leave whenever you want.

Within three months she decided she wanted to live here but the center of Shibuya is not a place for humans to live. She and got an apartment in Kugayama and I temporarily moved in.

Kugayama with Amy - 2022

While living in Kugayama, my podcast team found ourselves suddenly understaffed and in a pinch. Luckily, I lived under the same roof as someone who would be a great addition to the team—Amy. She’s a great writer and knew the ins and outs of the reporting just from living with me so she was hired, tentatively at first. Then enthusiastically.

Living and working with Amy was one of the happiest times of my life. We would sit at her little dining room table and brainstorm story structure, workshop lines we were stuck on, and when we needed a break we’d walk along the river and look at ducks. After work every day we’d watch an episode of Hunter x Hunter and drink sake from little cups.

I left my family home when I was 14 so I hadn’t lived with my little sister since she was 9. Back then she was a nail biting know-it-all kid and now she was a nail biting know-it-all adult who also made great cocktails, generated endless puns and was a delightful co-worker.

After many setbacks the podcast came out in December and I headed off to South East Asia for a couple months. It was intoxicating to go so far and wide after spending the better part of a year in a small apartment remote working. When I came back, I immediately found my own place but made sure I wasn’t too far away from Amy. Hanging out with her is still one of my favorite things about living in Tokyo.

Asagaya Arcade Apartment - 2023

When I was looking for a new apartment I happened to get coffee with my friend Jamie who lives in Koenji. I told him about hunting for a new neighborhood to live in. He said, “Let’s go for a walk,” and took me to Asagaya, one station away from Koenji, because he thought I might like it. I took to it immediately: Star Road with the little bars, a shopping center with a roof so I could shop in the rain, the writers and anime artists working away in the cafes.

I moved there within a week. I became a regular at many cafes, bars, shops and galleries and not since Hiroo was I so invested in my neighborhood. Within a year, I almost never left the house without seeing someone I knew. People were friendly in Asagaya and had time for you — a rare thing in bustling Tokyo. I was also fond of my living space — it wasn’t huge but it had everything I needed and a view of Shinjuku in the distance. I loved bringing a drink up to the roof to watch the sunset. Life got busy in a good way while I was there: friends from out of town visited frequently, I started a second true crime podcast and I moved a sound studio into my apartment.

To be honest, I was not prepared for so much living and working and entertaining to take place in my humble studio apartment. I ate, cooked and worked on the same counter as my monitor, dish drying rack and coffee maker. I figured that I could deal with it until the lease was up. I started envisioning what kind of apartment would be the one that I would stay in for longer than two years. It would be larger, it would be right by a park, and it would have separate spaces for sleeping, cooking and working.

I didn’t exactly get to apartment hunting because I met Ibuki. His approach to dating me was not unlike someone trying to tame a stray cat — no sudden movements, lots of treats, heaters and lights arranged in ways I might find pleasing. He recently admitted that two months into dating, he bought a tall kitchen stool because I had a habit of perching on the kitchen counter. To his dismay, I was indifferent to the stool much like a cat who chooses a cardboard box over the nice cat bed. His stool plan may have failed but his dating strategy worked: we met in the fall and by summer I moved into his apartment.

Chitosefunabashi - 2024

Now we’re caught up. I’ve only lived in Chitosefunabashi for a month now. The first week I was here Ibuki could be found making endless shelves for the new spices, clothes and books I brought in. I have a work space, a dining room table, a large kitchen, a bedroom. Kyoko has a lot of room to fly around. The place feels homey and we are both happy here. It is the cherry on top to split rent. BUT here is the kicker — the apartment building is getting torn down in December.

In other words, we have to move very soon.

I am thinking again of my perfect apartment — how long I’ll get to stay there is up to fate.

?? - 2024

To be determined! If you came along this far, thanks for taking an abbreviated ride through my life and times in Tokyo. Lots of love to everyone whose been a part of it

So so happy to read this Shoko! I love your words, and I love your writing. Please pleaseeee write more <3

Absolutely loved this! Thank you for sharing x